Plenty of digital ink’s already been spilled about the Apple Watch. Most of it said “it’s not for everyone,” which completely misses the point of reviewing a product. Most of it also completely missed the point on what’s actually good and bad about the product itself.

Here’s Part One of three thoughts on the product’s present and future.

Part One: “It’s not for everyone” — Every tech journalist on the internet

This narrative sounds like it was directly ripped from The Emperor’s New Clothes.

Here’s some link soup borrowed from Rusty Forster’s April 8th delivery of Today in Tabs.

Oh hey it’s Apple Watch review day … Farhad says it isn’t for everyone. Re/code says it’s kinda like other smartwatches but that doesn’t mean it’s for everyone. Topolsky says it probably isn’t for everyone and also demonstrates that checking your watch makes you look like a huge dick. The Wall St. Journal says that “[w]ith the Apple Watch, smart watches finally make sense,” but that it isn’t for everyone. The New York Times calls it “Less Than Fulfilling,” and points out that it probably isn’t for everyone. The Verge made a review so pretty I am unable to read any of it, but I think the gist is that the Apple watch is only for some people, not all the people. And if you only have 4:30 to figure out whether you want one, watch Joanna Stern’s video, which certainly makes it look like the watch isn’t really for anyone.

The Verge spent 6700 words to give the Watch a “7” out of 10 — which is to say, they spent 6700 words to say nothing. “It’s not for everyone” says nothing.

It feels like everybody is too afraid to look silly in front of their peers and their tech overlord Apple to articulate what’s plainly in front of them: “This product is not very good, and the Emperor is standing in there in the buff.”

So I’ll say it: I don’t think getting notifications on your wrist is helpful or productive. I don’t think calling or sending quick canned message responses to people from your wrist is interesting or time-efficient. I don’t think these features make for a compelling product, and they especially don’t make for a compelling watch. And I don’t even think you need to demo the watch for a week to come to this conclusion. It should take seconds.

Of all that word vomit across every tech website, I think the very most important quote is this one line in the John Gruber Daring Fireball review:

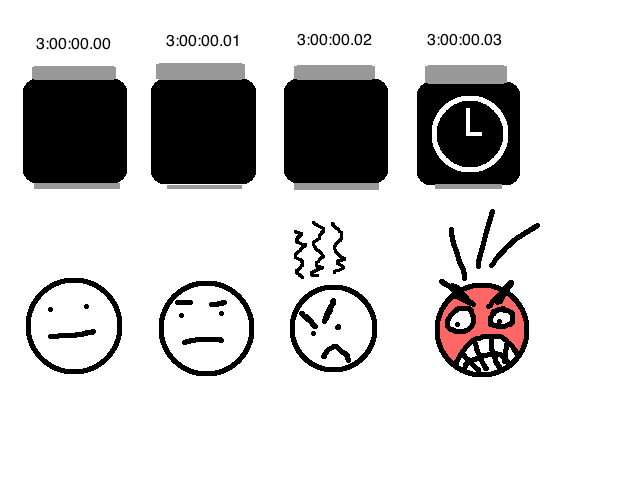

There’s an inherent tiny amount of lag that isn’t there with a regular watch.

Gruber is saying that it takes a split second for the Apple Watch accelerometer to realize that it’s being summoned and to wake up. I don’t think he means for this to be a big deal, but to me, this split second means everything.

I’m a zealot about use cases and User Experience (this is why I do Product Management for a living), and as an avid watch user myself, there is one very explicit, defining, and specific reason for wearing a watch: To tell the time, not to a fraction of a second, but in a fraction of a second.

Read that again, and then let’s unpack it. To tell the time, not to a fraction of a second, but in a fraction of a second.

“To tell the time…” obvious.

“…not to a fraction of a second…” According to Daring Fireball, Apple is advertising that its watch is accurate down to five hundredths of a second. Maybe this is important for molecular physicists? I don’t think anyone else really cares. My primary watch, like many perfectly functional wristwatches, doesn’t even have a second hand.

“…but in a fraction of a second.” I wear a watch so that I can glance down during a meeting, or mid-conversation, or while I’m walking, or as I’m writing this very post, or anywhere, and know the time without having to wait or fidget or lose my stream of thought. That process time and that lack of cognitive interruption are vitally important.

Introduce even the most minuscule amount of lag (or even a “Sleep” timer, or anything like that) and the Watch’s primary use case is crippled.

Gruber draws out a few other illustrations:

I wanted to catch a 4:00 train home to Philadelphia. I was sitting on a low bench, leaning forward, elbows on my knees. It got to 3:00 or so, and I started glancing at my watch every few minutes. But it was always off, because my wrist was already positioned with the watch face up. The only way I could check the time was to artificially flick my wrist or to use my right hand to tap the screen — in either case, a far heavier gesture than the mere glance I’d have needed with my regular watch.

Similarly, it turns out I regularly check the time on my watch while working at my desk, typing. I didn’t even know I had this habit until this week, when it stopped working for me because I was wearing an Apple Watch. Again, because in this position the watch face is already up, the display remains off. My wrist doesn’t move when I want to check the time with my fingers on the keyboard — only my head and eyes do. And yes, my Mac shows the time in the menu bar. I can’t help that I have this habit, and Apple Watch works against it.

Here’s one more scenario. I grind my coffee right before I brew it. I put a few scoops of coffee in my grinder, cap it, and press down with my right hand to engage the grinder. I then look at my left wrist to check that 20 or so seconds have expired. But with Apple Watch, the display keeps turning off every 6 seconds. There are ways around this — I could switch to the stopwatch, start it, and then start grinding my coffee. But my habit is not to even think about my watch or the time until after I’ve already started grinding the beans, at which point my right hand is already occupied pressing down on the lid to the grinder.

This is how watches are used. Everything else is secondary to this. Apple Watch fails — and fails hard — at being a wristwatch. (Did they not do live user testing? Wouldn’t this stuff have come up almost immediately?)

It’s rare, but not unheard of, for a new product to perform underwhelmingly in its core use case but have other value propositions more than compromise for this shortcoming. A large chunk of Clay Christensen’s seminal book The Innovator’s Dilemma discusses the microprocessor industry, and explores how new companies built processors which were much weaker than incumbents — but whose advantages in size and price enabled them to find new profitable customers and use cases.

I don’t see those advantages or use cases here. And because of that, here’s the score that the Apple Watch today deserves:

Score: 2 out of 10

The Watch gets a 0 out of 10 because it fails to do what it is explicitly supposed to do: be a wristwatch. Then it gets two charity points (not 7, The Verge!). One because the Watch is an interesting new thing that if you buy it you will impress people at your office’s water cooler.

Who is this watch is for? Not for “not everyone,” but for people who have blind faith in Apple products — and if that’s you, then you didn’t need any review of any length to aid you in a purchase decision.

The other charity point I’ve awarded because it’s obvious that there’s potential here for something much greater than what we see today.

(That much… we’ll discuss when we get in to in the much more positive and forward-thinking Part 3.)