Part I: Tidal’s failure has nothing to do with PR

People hate Tidal.

It’s an easy target. The launch event was the most noxious PR move we’ve seen anywhere since LeBron took his talents to South Beach, and a nauseating event like that deserves every ounce of disrespect it continues to receive.

But a product getting marketed poorly doesn’t necessarily mean it’s abysmal. (Consider that, in LeBron’s case, the Heat actually turned out to be a pretty talented ballclub.)

So in light of all of the Tidal hate, I wanted to try to write the most hopeful, constructive, and maybe even at times positive review of Tidal.

This wouldn’t be easy.

Tidal does have two pretty meaningful structural problems: Buffering and video.

In 2015, if your music app has to pause mid-song to buffer, you’re dead in the water. There’s too many competitors out there, and no amount of bonus features are going to counteract the lurch of your speakers going completely quiet out of the blue, waiting for data to load.

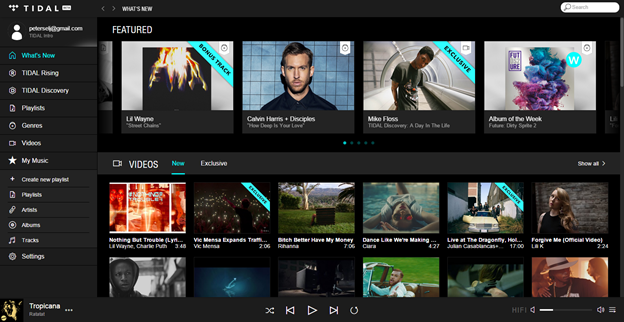

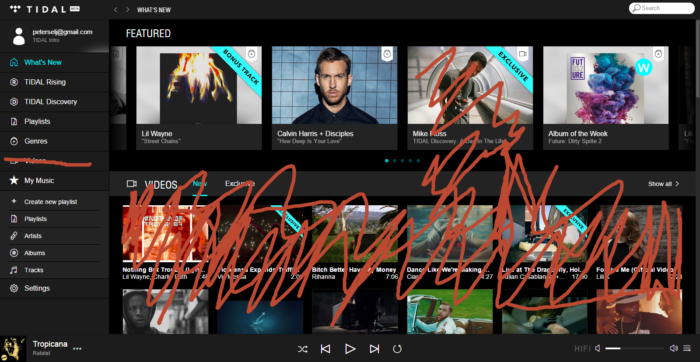

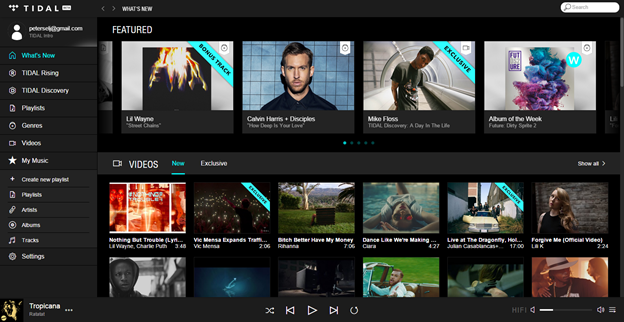

And video… well, devoting ~ 50% of the landing page real estate to video is a disaster.

This screen space is just too important to devote to an idea which fundamentally splits Tidal’s use case in half. We already proved once that the world wasn’t ready for a combo music/video platform, and that was just two years ago.

With those cleaned up, we can focus on Tidal’s philosophy, and really figure out what went wrong and how to fix it.

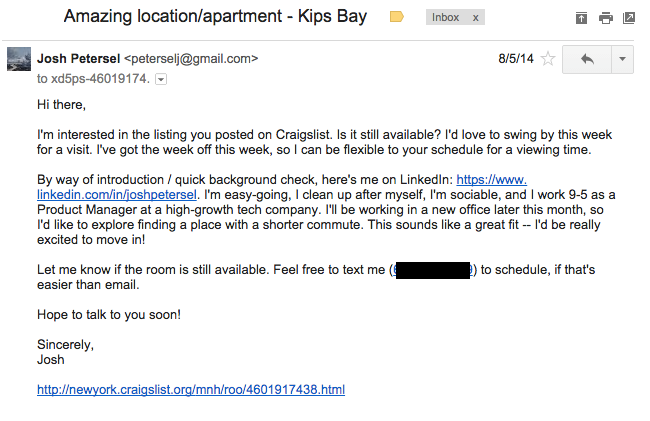

“For Artists by Artists” is a dumb idea, right Josh??

No, I actually think “For Artists by Artists” has the potential to be a really great idea.

In fact, I think Tidal has the potential to be three really great ideas. It just doesn’t seem to know which of the three ideas it should be:

- For audiophiles who feel robbed by 320kpbs bit rates

- For artists who feel robbed by Spotify’s payouts

- For geeks and elites who feel robbed without exhaustive/exclusive info

Any one of these could be a fine launching point to build a niche, cult following and eventually build into a massive, attractive consumer platform. Instead, Tidal says nothing but “yes” to all ideas. In trying to appeal to everybody, Tidal winds up losing on all fronts.

(Maybe it’s just that nobody at company headquarters just had the balls to say “no” to Jay Z at any point?)

Tidal’s failure has nothing to do with PR, and everything to do with ineffective product management & strategy.

We’ll spend the next three essays diving deeper into how specifically Tidal failed at each of these three core initiatives, and thinking about, if executed properly, how a platform like Tidal might be redeemed.

Part II: High Fidelity, and… Pepsi

What’s the difference in Sound Quality between Tidal, Apple Music, and Spotify?

According to The Verge… nobody has any idea.

Tidal’s challenge is to innately understand its users — and specifically, in the case of Sound Quality, to understand its use cases.

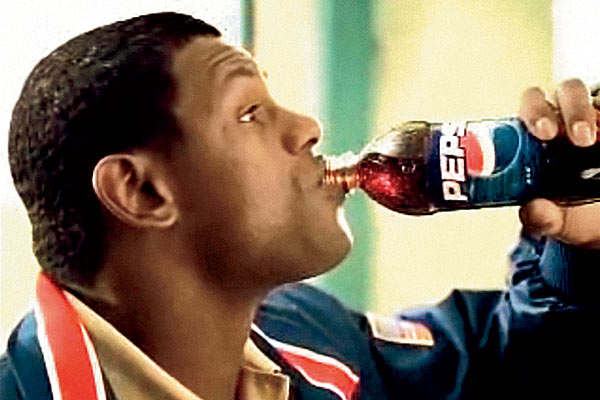

In the video above, you’re inclined to conclude “these all sound the same; therefore, Tidal’s HiFi is a wash.”

The more scientific conclusion is that “these all sound the same under these specific conditions; therefore, under these specific conditions, Tidal’s HiFi is a wash.”

The difference (“under these conditions”) is subtle but profound.

At the end of the video above, the host disclaims that they tested using an average mobile phone and mediocre headphones. The quality of this listening experience is handcuffed to the quality of the hardware and surroundings. These are confounding variables.

Background:

A confounding variable is when an extraneous thing that you weren’t testing for skews and affects the things you were testing for — so your results are fundamentally flawed. In the case of the study above, concluding “all these songs sound the same” using mediocre headphones is kind of the same as concluding “all this art looks the same” if you were walking around in a museum with all the lights off. The lights being on or off is a confounding variable which affects your ability to perceive art.

Unfortunately, most members of the public (and apparently many members of the media) won’t think of this. Which means that unless Tidal does something substantial, it will be impossible to differentiate itself on Sound Quality.

Did Tidal not anticipate that this is how their users would behave? A company like Tidal could learn this by studying how people actually use their product — not in focus groups, but in real-world observation through human-centered design. They’d see that listeners are often in subway cars. Or they’re half listening, half swiping through their email inbox or text messages or Tinder profiles. They’re almost definitely using crummy $15 earbuds.

No number of audio bits per second is going to drown out the hysteria of a daily commute or the adrenaline of a Tinder match. Despite being a better product, Tidal and Spotify and iTunes will all be indiscernible.

Okay fine, Jay. If you insist on having Tidal rely on an unprovable use case like “it sounds better,” we can do that. We can even do that and still succeed. It’s even happened before.

Tidal just has to become Pepsi.

Step One: If Tidal wants to be the platform for audiophiles, it must understand its use case and make it disgustingly clear: “This is the kind of home audio system you need, these are the kind of headphones that make this worthwhile. Otherwise, don’t bother.”

This kind of pitch is brutally honest, and so narrow and exclusive that it unquestionably forfeits market share in the short-term. That’s okay. Maybe better than okay. Maybe even a strength. In fact, many of the best minds in tech suggest that starting by building for a very narrow niche rather than appealing to the general market out of the gate is the way to win in the long run. Focusing on such a narrow use case often affords you the benefit of being casually dismissed by competition and the media… until it’s too late. (Remember when Uber was just a black car service?)

More importantly, it gives Tidal an opportunity to focus on a narrow set of needs, and build differentiating features which would be impossible for mass-market competitors to compete with.

How do you get the people like Rob Gordon from High Fidelity to switch to Tidal?

Background:

Rob Gordon, the protagonist of High Fidelity, takes the time to reorganize his monstrous record collection in autobiographical order — that is, in the order in which he acquired each record. It’s unbelievably painstaking and neurotic; yet, he takes the time to do it. And his colleagues are mesmerized.

In Rob’s case, make it easy for him to organize autobiographically — maybe a separate column where the user can enter her own autobiographical data next to each album. More generally, find eight people who care about music like Rob Gordon does, follow them around, and figure out all the other the neurotic things they do like autobiographical order which technology can do better, and build for that.

Nine times out of ten, mass-market solutions of the world can’t compete with that, because there’s no economic case to build for Rob Gordon when they’re responsible for building for the mass market.

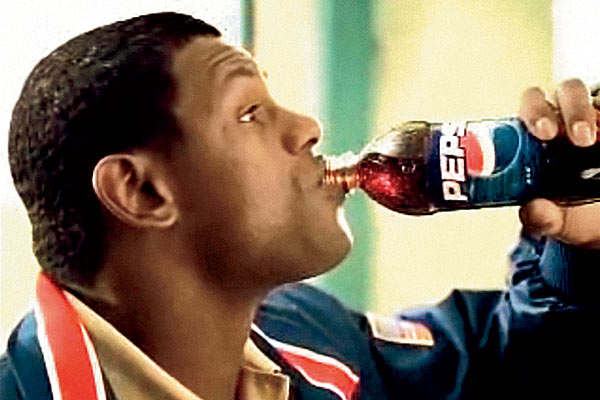

Step Two: Once Tidal has a narrow but zealous following, Tidal can become Pepsi by launching its own Pepsi Challenge.

Background:

In the 1980’s, Pepsi said “Do a blind taste test between Pepsi and Coke, and you’ll like Pepsi better.” This was true. It turns out we tend to like Pepsi better in taste tests, because it’s slightly sweeter and slightly more bubbly.

The thing is, nobody actually drinks cola in small taste-test fashion — we drink it in 20-ounce bottles at home and souvenir cups at ballgames. When you study how people actually consume soda, they prefer the slightly blander, softer taste of Coke. But it didn’t matter. Pepsi gained critical market share, Coke panicked and made New Coke which sucked (even though New Coke “tested” better than Pepsi) and led to Coke ceding even more critical market share.

In the cola case, Pepsi had a worse product than Coke, but acutely understood what its products strengths were and carved a path to monstrous growth. Tidal could be Pepsi, but not if it just says “hey try us out, we taste better.” It needs the Tidal challenge. It needs to create the setting — down to the headphones, seating, and environment— where its product is unquestionably better than the rest of the field.

In fact: Tidal has in an especially ripe opportunity to position itself above Apple, in the wake of the Beats acquisition. Beats are notorious for being gaudy headphones with middling technical performance. Apple irreversibly and conclusively compromised on audio quality. A Tidal partnership with Sennheiser or Bose and a direct frontal attack on Apple’s audio quality should have been a grand slam among both actual and aspiring audiophiles.

Conclusions

- When you’re building a product, test things scientifically. Understand the dangers of confounding variables

- Start with a narrow niche where you can build something that solves very deep pain or creates monumental unique value. Tidal should concede the mass market and focus on the Rob Gordons

- Intimately understand use cases to learn your actual strengths and weaknesses as they compare to your perceived strengths and weaknesses. Tidal must know that its quality is impossible to perceive when listeners are using average equipment in everyday situations, and build and market itself accordingly

- From those last two, build on a value proposition that isn’t even a comparison — it’s unwinnable for anyone else. Tidal should launch the Tidal Challenge and let the results speak for themselves

Part III: For Artists, By Artists

The most common criticism about Tidal’s “For Artists” claim is that its payout structure still offers roughly a penny per track played — functionally equivalent to the rest of the music x tech field. This complaint comes from a real pain, but I think it’s a bit misguided.

As consumers, we obviously all saw through the launch party event and agreed that the artists we wanted to support weren’t the multimillionaires on stage, and nobody thought the world needed another Planet Hollywood.

*Sigh*… all right, fine, Jay. You have to pick one, but if you want FAbA instead of High Fidelity Audio, and you’re sure of that, we can do it.

Tidal can be the For Artists by Artists platform and do a better job supporting the actual artists we consumers all want them to. But first, we have to understand the mechanics under the hood.

CAUTION: MATH SECTION

Most platforms do payouts like this, roughly: (Platform Net Revenue * Quantity of Artist Song Plays) / Total Plays of All Artists on Platform. So payout rate isn’t something the platform (or anyone) directly controls. Instead, there’s three variables we can manipulate to try and work in the favor of the artists:

1) Platform Net Revenue. Which is roughly (# Paying Users * Monthly fee). To make this variable go up, you either need more users or need each user to pay more per month. Naturally there’s a tradeoff—the more you charge, the fewer customers you tend to attract. (The platforms could also theoretically work out better deals with the labels and reduce their operating costs… but ugh, let’s not talk about record labels)

2) Quantity of Artist Song Plays. The more spins an artist gets, the more it gets paid

3) Total Plays. Somewhat counterintuitively, if there are fewer artists on the platform, if users are less engaged in the platform overall, the denominator of the revenue calculation gets smaller, and the payout for a given artist gets bigger assuming their Quantity of Song Plays remains constant

Spotify makes #1 go up by employing a freemium model which attracts lots of users and subsidizing costs with advertising. Tidal makes #1 go up with its HiFi product which charges $20/mo instead of $10. These initiatives are both in the interest of artists.

I’ll say that again: Spotify’s Free tier and Tidal’s Premium tier are both in the long-term interest of artists because they’re both designed to increase #1: Platform Net Revenue.

But then…

Each platform provides exhaustive tools for new artists to onboard, and for users to discover new artists. This is a double-edged sword. New Artist & Discovery features are helpful to artists for #2, but damning in terms of #3.

CAUTION: MATH SECTION II

Say, for example:

– If 10,000 artists can get 1,500 plays each, they each go home with about $15.

– If 100 artists get 150,000 plays each, they each go home with $1,500.

(Conveniently, $1,500 should be just about enough for an artist to cover studio time + mixing.)

At first, 150,000 plays feels like an incredibly unreasonable number of plays to reach just to cover studio time. But that feeling is based on human logic which hasn’t yet adapted to the scale of the internet. Most artists — most regular humans — think in and react to terms they can readily grasp and understand. There’s this quote often attributed to Joseph Stalin, “A single death is a tragedy; a million deaths is a statistic.” That’s how humans, artists among them, are inclined to think. “A penny per track is a tragedy; access to 60 million listeners and getting 150,000 plays, a statistic.”

So at Tidal, if I wanted to be For Artists by Artists, maybe I’d spend my time thinking less about helping users discover new music, and more time thinking about getting users to be loyal to and excited about fewer, specific musicians, and helping those specific musicians be discovered by more loyal fans.

Maybe this means Tidal doesn’t have the world’s most exhaustive library. Instead, maybe Tidal’s got a very carefully curated list of artists who it thinks its listeners will like. This might mean ceding the potential base of listeners who just want to “Discover,” and being unable to support the very long tail of artists, and instead focusing on immersive, intimate experiences so that users can ramp playcounts up for the chosen few.

It’s possible that being a discovery platform is actually toxic for artists — that what artists really need is a loyalty platform.

Guess what: The “discovery platform which everyone thinks they love actually turns out to be a raw deal for content providers” thing isn’t a new phenomenon.

Check out what Mark Pastore, owner of a high-end restaurant in San Francisco, has to say about OpenTable. Here’s some select quotes:

Let me start by stating the obvious: the convenience and immediacy of booking a table online anytime day or night is beneficial to both diners and to restaurants …

It’s possible, however, for convenience to come at too dear a price …

customers [are] loyal to OpenTable, [and] restaurants find that they themselves no longer own the customer relationship.

Restaurants rely on the patronage of loyal customers whose continued engagement, conceivably, leads to a) bigger and bigger checks, b) louder word-of-mouth, and c) better-behaved patrons who restaurant owners genuinely like working to please. The platform promises new patrons, providing restaurants with theoretical access to millions of prospects, and providing the prospects with a gluttony of tools to discover the next new thing. Patrons use the platform to shop around, grow loyal to the platform, grow distant from restaurants individually.

Now, replace “Restaurants” with “Musicians,” and you’ve got a clear-cut illustration of how the modern music/tech industry works, and why every artist not named Taylor is having trouble shaking it.

Unfortunately, nobody in the restaurant industry has really figured out how to take down OpenTable just yet.

Maybe, I wonder, it’s just as simple as the fact that nobody truly influential enough has called the present-day Discovery model out on its destructiveness. Mark Pastore may be an influential restaurateur and known in select circles, but face it: you had no idea who Mark Pastore is.

…So if only we knew someone motivated who could make an audacious claim like “discovery is killing artists,” and rally a lot of influential troops behind him…

He could explain that the way to help your favorite artists succeed is to be loyal to them, and he could build a version of Tidal that encouraged and reinforced loyalty instead of discovery.

CAUTION: MATH SECTION III

The crux of the problem here is about math, but also about human intuition. On a purely monetary basis, the following two should be equal in value for an artist:

– 1,500 listeners who play one of your songs once this month

– 10 listeners who plays your songs 150 times this month

It should be obvious without even getting into any advanced math, though, that bands would prefer the second group of fans over the first — the latter is more likely to continue listening in months down the road, more likely to buy other products and tickets, more likely to engage with the content creator directly. On that basis, artists should seek tools and platforms to attract loyal listeners rather than fleeting listeners.

There’s problems, though. There’s the problem that loyal listeners and fleeting listeners kind of look the same when they first show up. More importantly, it’s MUCH harder to track and attribute success in converting a “New Listener” to a “Loyal Listener” than it is to track and attribute the conversion from non-listener to “New Listener.”

It’s easy and obvious on a human level to say “Tidal drove 1,500 new listeners to you this month,” because, well…there they are. And you can report that immediately, as soon as those listeners show up. For Tidal to say “we created 10 Loyal Listeners for you,” Tidal would at least have to wait around long enough (months?) for you to gauge loyalty, but also, Tidal has to convince you that it was something they did to create this longevity, rather than something endemic and catchy about the artist or her music.

So the incentives are screwed up. Tidal (and the rest of the music x tech mix, and OpenTable, etc.) all chase the Discovery metrics to which they can gauge and relate, and most unsophisticated artists play along because “new listeners” metrics makes sense. In so doing, the platforms are obliterating listener loyalty.

So how might a platform like Tidal engender listener loyalty and longevity?

- Leaderboards and points for being a top listener to a given artist in you zip code, in your region, overall (like what Foursquare does)

- Visible benchmarks (or even rewards!) for listeners which illustrate where bands need to get in order to achieve certain states of viability (like what Kickstarter does)

- Storefront to buy stuff directly from bands (like what BandPage does)…

- …or even just directly donate to the bands themselves (like what Patreon does)

I’m not sure that any of the features above are real breadwinners. Googling “how to create customer loyalty” brings up 14.5 million alternatives to what I’ve proposed. Customer loyalty is really hard.

So instead of a gimmick, or a new revenue model, I think it just comes down to Jay. Jay’s got to want it.

Jay Z is the kind of force who, maybe, can engender loyalty just by saying “This is who I listen to. This is who I think is great.” Maybe Jay’s blessing is a self-fulfilling prophecy — he predicts a band should be listened to a lot, and it gets listened to a lot because of what he suggests as much as anything else. The narrative of the Tidal platform has to be flipped, from “discover a ton of new music here,” to “discover just a few bands to go really, really deep on.” The weekly update email isn’t “here’s this week’s latest releases,” but “here’s some new perspectives on that album you heard, and how everything gets better if you listen again.” Jay needs to make it sexy for people not to say “Hey, check out this new track I discovered,” but to say “I can’t believe how much better and deeper Tame Impala has gotten now that I’ve been listening for two weeks straight!”

It’s possible that this model is bunk, because almost no music is good enough, or broadly appealing enough, to warrant such substantial play. Or that there’s just too much good music, and no real upside any more for fans to do anything but continually bounce around.

Personally, I’m not the kind of music enthusiast who takes deep pride in listening to bands you’ve never heard of. I’d rather listen to, say, just twelve bands — but really, truly, deeply give a damn about each one of them. The kind of relationship where you’re compelled to fly across the country to see the finale show of their tour. Better yet if those are the same twelve bands I know my peer group is listening to as well. But maybe that’s just me.

Conclusions

- Despite the popular narrative thinking otherwise, Tidal and Spotify Freemium are both actually designed to be For Artists

- What really kills artists, and content creators across numerous verticals, is the obsession of platforms tracking “Discover” and “New Listener” metrics

- To really be the For Artists by Artists platform, Tidal needs Jay Z to lead a push, a narrative, and a set of user tools designed for artist loyalty

Part IV: The Magazine of the Future + Overall Conclusion

Jay Z’s last desire, which we outlined all the way back in Part I, is that Tidal should be the go-to resource for the most devout music consumers in the market — those who want content that’s both exhaustive and exclusive.

It’s pretty hard to be a thought leader and get recommendations right — in any space, but especially in the music space. That’s why there’s thousands of blogs, companies, and algorithms all trying to accomplish the same thing.

Tidal fails at the Exclusive Content value proposition because their “exclusive” stuff is all over the map. Look again at my landing page:

Lil Wayne + Calvin Harris + Julian Casablancas + Lilli K = I don’t think you have any idea whatsoever about what I want. There’s no voice, structure, theme — you’re hitting me with the kitchen sink.

To be fair, algorithmic recommendations engines take a little bit of time, and in my short 2-week trial, it’s feasible that Tidal simply didn’t have the requisite base set of data to be able to produce meaningful results.

I’ve personally never been a huge fan of algorithmic recommendations. I tend to opt for things that are a little more… human.

So, for the sake of argument: What if Tidal thought, talked, positioned, and designed itself like… a magazine?

I’m obviously a little biased here. But without an editorial voice, the fact that Mike Floss’s video above is “Exclusive” means absolutely nothing to me. “We’re the only platform that has this Mike Floss stuff” doesn’t necessarily equate to “You should really want it.”

I wonder what would happen if Tidal vertically integrated, and acquired a prominent music magazine like Pitchfork. What if the magazine and the streaming provider were one in the same, both rented for the flat $10 fare?

Netflix is a shining example of a vertical integration being implemented to great success. They integrated up the chain, becoming creators and producers to complement their distribution. A music player following suit isn’t an unheard of idea, or a terrible one. This integration we’re considering would go down the chain — Tidal would become distributor plus critic.

My biggest question (shaded again by my magazine background): Would an acquired magazine’s editorial integrity be compromised by being the primary content player as well as the editorial writer? I don’t think so; at least, no more than editorial is usually compromised by the needs to get clicks, page views, and ad conversions.

In fact, it’s possible the Tidal Magazine model would allow for even better, more authentic, more aligned content than any of its peers.

The primary job of a music writer is thus: Inspire your reader to listen to the subject matter (album, artist, etc.) at hand. In a world where content is paid for by ads, the writer and the magazine employ tricks to ratchet up ad views: clickbait-y titles, articles spliced into 17 slides. It’s better for the advertiser and for the magazine if the reader clicks through five different quick pieces and sees five different BUY A FORD TRUCK ads. The reader’s experience and the author’s objective are compromised. As we discussed last time, the artist is marginalized as well by readers who are more inspired to flake around than hunker down.

In Tidal Magazine world, however, the publisher gets paid the same $10/mo no matter how many articles are viewed. Authors can be measured directly by their ability to convert article reads into album listens. The interests of the author, reader, and platform are all aligned. Instead of A/B testing articles for their titles’ clickbait-y-ness the magazine might A/B test the actual content of the article, and measure not views but conversions.

Many premium websites already sustain themselves by charging $10/mo just for access to the written content. I’m fascinated by the prospect of a sophisticated paid platform with an actual revenue-generating product behind it.

This website estimates Pitchfork is worth $83M . This website has them at 12.9M (as of 2011). Neither figure is really a serious amount of money in the Venture Capital backed, winner-take-all economy that the music media platforms live in. (Consider that Spotify acquired Echo Nest for $100M to enhance its recommendation platform, for comparison.)

To improve its platform, to really differentiate from a functionally indistinguishable crowd, to align participants and really get down to Jay Z’s root interests, to take a crazy shot at winning in what appears to be an increasingly desperate fight… I don’t know, this seems like a good deal.

Conclusions

- Good content is hard to create and hard to curate algorithmically

- But it’s probably not that hard to acquire

- Tidal could differentiate by becoming (acquiring) a magazine. It’d be unique in its position to align the interests of writer, reader, and platform: All towards converting articles to song listens, without the distraction of ad views

OVERALL CONCLUSIONS

- We learned why Tidal Sucks: Its mission statement was all bark and no bite. We talked about the importance of product strategy, about the impracticality of trying to be everything to everyone, and about how much better it is to stick to one mission and kill it

- We discussed how Tidal might approach High Fidelity Audio, about what makes that particular value proposition difficult, and about how Tidal might thrive on even a fake competitive advantage anyway by harping on use cases its listeners could really experience and relate to

- We employed some math and psychology to learn why artists aren’t impressed by Tidal’s compensation. We explored some steps Tidal could take to make its platform more appealing and sustainable for up-and-coming artists, and could differentiate Tidal’s platform from the rest of the music discovery field

- Finally, we dove in to the premise of exclusive content, and explored an the merits of buying a media platform rather than trying to build one themselves