Some tablesetting to make sure we start from the same page:

- “Print is Dead; Long Live Print” etc., according to pundits everywhere.

- I used to work in print. So you might argue that I’m biased. I’d argue that I’m just passionate about the space.

Given the above, I find myself thinking about the future of print media quite frequently. I wanted to present a few thoughts.

First: We need to better support the idea of “progress.” Not “progress” in the chronological or Darwinian sense, but “progress” in the sense of “how much of this article do I still need to read?”

Right now, if you want to write something on the internet longer than 140 characters, your best bet for success is a Top 20 list. Buzzfeed.com nails it on this. Cracked.com had its heyday, too.

There are plenty of arguments for why lists work. Here’s a list article on why list articles work. (Wow, so meta.) It argues that lists make for attention-grabbing headlines. You can also argue that it breaks content up into bite-size chunks, which people need because they’re theoretically now more distraction-prone.

Here’s my favorite feature — by far — of list-based content: It gives me a progress bar. It affords me a guess as to how long this is going to take and how far I’ve come as I’m poring in. So when I’m reading something like, I don’t know, 10 Ways Wall Street is Just Like Sesame Street, I have an internal sense of how close I am to completion. I’m not actively monitoring it, but I’m passively aware of it.

And as enjoyable as it is to read lists, the pleasure pales in comparison to the euphora of completing a list.

For a regular internet article, it’s rather difficult to gauge how much reading you’ve got to do. Even list articles that aren’t all quick hits like “Here’s 20 Cat GIFs!” are tough to gauge. (In case you’re wondering now, you’re about 20% done with this blog post.)

Classic print used to have this baked in. You didn’t need explicitly need a progress bar — you could gauge it yourself by observing the the weight and size of the pages.

A few platforms that do make it easy — or otherwise leverage the idea of “progress” –exceedingly well:

- Medium.com. It’s the only place on the internet that comes to mind where each article has an expected time length explained right up front. This article about LEGOs is going to take you ~5 minutes to read. Not that I expect you to set a stopwatch before opening it. But I do expect your internal clock will guide you, and that you’ll feel satisfied when you complete your task within the allotted time.

- Bleacherreport.com. They do this maniacal thing with lists where they’ll write “Page X of 34” at the top of a 33-page article, and I’ll be so driven to complete the list that even when I’m on what’s clearly the last page (for example, the Seahawks were the #1 team in the NFL Power Rankings) I’m still driven to go to the next page — and will subsequently find myself on the next article.

- The Amazon Kindle has a progress bar at the bottom of every document to let me know what page I’m on or my percentage completion. It’s delightful.

- Feed readers, like feedly.com. Feedly explicitly tells me I’ve got four unread articles left from TechCrunch. It automatically counts down as I careen through each update, and it automatically repopulates as the day goes on and new content is posted. Finally arriving at “TechCrunch (0)” ? Zen.

Second: Embrace the Blockbusters. That’s the term coined by a really smart person I know to refer to superstars. Everything in media today revolves around the biggest, brightest 1% of talent. ESPN gets this, and it’s why they run a wildly disproportionate number of stories on LeBron James and Johnny Manziel compared to their respective athletic peers.

In the context of print, I understand there’s some tension. Is the “Blockbuster” the publication — say, Rolling Stone — or is it the author — say, Matt Taibbi?

I think the world is moving in a direction where the authors are becoming the kings, and the smart media entities are embracing and investing in the blockbuster authors — which ensures that they’ve still got skin in the game.

Platforms that get this idea really well:

- ESPN. Who realized they had a blockbuster on their hands in Bill Simmons, and responded by giving him his own entire website in Grantland.com.

- ESPN, again. Who realized Nate Silver was a burgeoning blockbuster, so they hired him and are presently partnering with him to relaunch FiveThirtyEight.com.

Third: We need to better embrace the idea of being an “archive.” Back in print’s heyday you could print Yesterday’s News and accurately describe it as “Today’s News.” Classically, this was called a “Newspaper,” and classically, the primary value proposition was something like “this is the news as up-to-the-moment and relevant as possible.” It’s obvious now that technology has supplanted newsprint on the element of speed, which has consequently led to the masses writing off print.

So we need to re-consider the present and potential benefits of print. And where I think the medium really shines is in its ability to archive and catalog content. The heavy majority of online shortform content is ephemeral. It’s nearly impossible for me to look up a tweet I wrote a year ago — not that I’d really want to. Longform, however, affords the magical opportunity of being linked temporally. The New York Times has an archive dating back to 1851 — searchable on their site and I think at the public library.

Here’s what I’m also getting at: The difference of One Day is a pretty significant deal when we’re talking in terms of breaking stories. But when we’re talking in terms of archiving stories, the difference of a day pales in comparison to the importance of proper thought and consideration, of illustration, of context. For Longform to be successful, I think it really must harp on capturing “This is the complete picture of the way your world was at this point in time,” and defer to shortform media for the breaking stuff. With that perspective, I think I can better stomach the idea of waiting a day in exchange for assurances that A) This is important, and B) It’s been given careful thought and vetted for perspective.

A few platforms that do capture the idea of archiving well:

- Grantland.com. They produce the Grantland Quarterly, which is largely the same exact content that was already published on their website — but it’s revitalized with elegant graphics and print setting, and contextualized under the premise of “this is what it felt like to observe sports & pop culture for this 3-month window of time.” I think Pitchfork.com is moving into the same territory.

- Feed readers, like feedly.com. There’s a big difference between this and the social news aggregator types that seem to be en vogue these days — things like Flipboard, Prismatic, Twitter. With those, it’s nearly impossible to track and consume everything published by the sources that are most important to me. You can do it if you’re on the platform all the time. I’m not, because I have things to do. Feed readers let me pick the voices I want to hear and ensure I get all of it — I feel lost if I’ve missed even a single update from my favorite writers.

Fourth: Embrace more modern technology. For years we’ve been treating these computer screens as if they’re just iridescent pieces of paper. Which they’re not. Screens can do things besides put black words on white backgrounds. Things that make reading a better experience than anything even possible on paper. They can also do a lot of things which make reading a worse experience, so we’ll have to be careful.

Many people argue that screens make reading longform untenable because it’s unnatural to stare at what’s essentially a big, flat lightbulb for long stretches of time. I have to emphatically disagree here. Because otherwise the movie and TV industries would be dust.

Right now GIFs are en vogue. They’re prone to being cheesy and extreme (again, we have to be careful) — I wouldn’t expect a GIF-illustrated article to ever be published by an upstanding news source without derailing any sense of prestige and credibility.

But then… there’s cinemagraphs. Which are GIFs… but elegant. Cinemagraphs.com has a bunch. iwdrm.tumblr.com has a bunch from movies. They’re subtle, and often, beautiful.

There’s also HTM5, now — which better than anything up until this point gives us the power to really upend the idea that the screen is a piece of paper.

A few places that get this idea:

- Pitchfork.com. I link to their Daft Punk Cover Story quite often. (Here it is again.) It does so much, so well, and it’s the best digital experience I’ve ever had reading close to 4,000 words in a single sitting.

- Rolling Stone once published something similar.

- New York Times’ Snow Fall is the piece that started this whole conversation.

- The aforementioned Cinemagraph repositories.

Fifth: We need to think really critically about Product Placement. I know. Sounds sketchy. And dangerous. Nobody wants to threaten the integrity of their voice. I’m not proposing that.

I’m not the biggest fan of traditional display ads. They were fine and enrapturing when the idea was invented some 100+ years ago. If anything’s changed since then, it’s not our collective attention spans, it’s our ability to tune out non sequitur advertising. We’ve just got more experience doing it now.

I think longform is the last major medium to really adopt product placement, and it’s killing profit potential. Why is print so far behind? Arguably it’s because it’s more natural to employ product placement in other media. In Back to the Future II, Marty McFly isn’t just outfitted with shoes and a hoverboard, he wears Nike HyperDunks and rides a Mattel hoverboard. Maybe it’s easier to place product without appealing to or breaking the principal of Checkhov’s Gun — the idea that every element mentioned in a narrative should be necessary and irreplaceable. You can get away with flashing Marty’s Nike sneakers on-screen; it’d be far more difficult to surface in longform print without the reference feeling blatant and Checkhov-ey. If I’m reading BttF2: The Novel, I can get by on simply assuming Marty’s wearing generic sneakers; in BttF2: The Movie, he needed to be wearing something anyway, it might as well have been Nikes.

We recognized this gap years ago when I was running Eleven, and started developing initiatives to address it. I’m tremendously proud of our work with Scion, where we created a concept that was intrinsically linked to the car, and afforded ourselves the opportunity to talk about the car (which was thus a Checkhov’s gun) without having to force it, without it being a distraction, and without it hampering the objectivity of the story — which was about cities, adventure, and music. A few places that do this really well:

A few places that do this really well:

…umm, nothing else in print really comes to mind. I could be missing something; I’m not omniscient/clairvoyant. Maybe you’ll consider something like Coors Light Cold Hard Facts, where the brand is somewhat relevant in the title but the beer really has little to do with the content contextually.

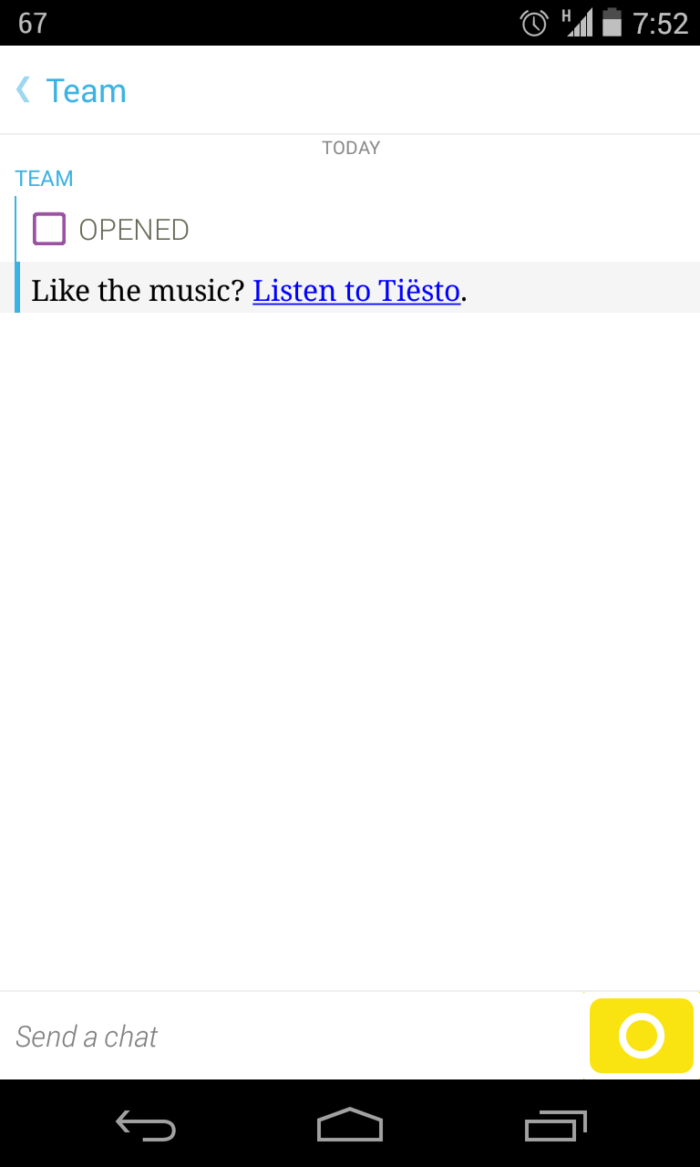

A recent trend is something called “native advertising” — these are the ads you’ll see if you use Facebook and Twitter on your smartphone, called “native” because they’re perched right inside your (otherwise content-filled) news stream. This is close.

A sponsored venue or setting seems to be the most reasonable opportunity for product placement. This was our angle with Scion — the venue was the car. Video series Always Open gets this with Denny’s. I think Jerry Seinfeld’s Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee has the potential to accomplish the same thing — which is ironic, given that the show is pointedly about being in cars and drinking coffee.

Sixth: Perhaps we’d better call it “Longform Media” instead of “Print Media.” Because I don’t think a war based on medium — print vs. digital — is winnable if you’re anti-technology. A conversation around content length however is I think inherently tenable, now that technology is sometimes on your side.

Conclusion:

You know, I usually like to make lists that are eleven items long, but this already turned into a 2,000-word behemoth. Print is an exciting place. I’ll be eager to see what the future holds.